Fiction Editing Chaper VII, Author: Pat Dobie

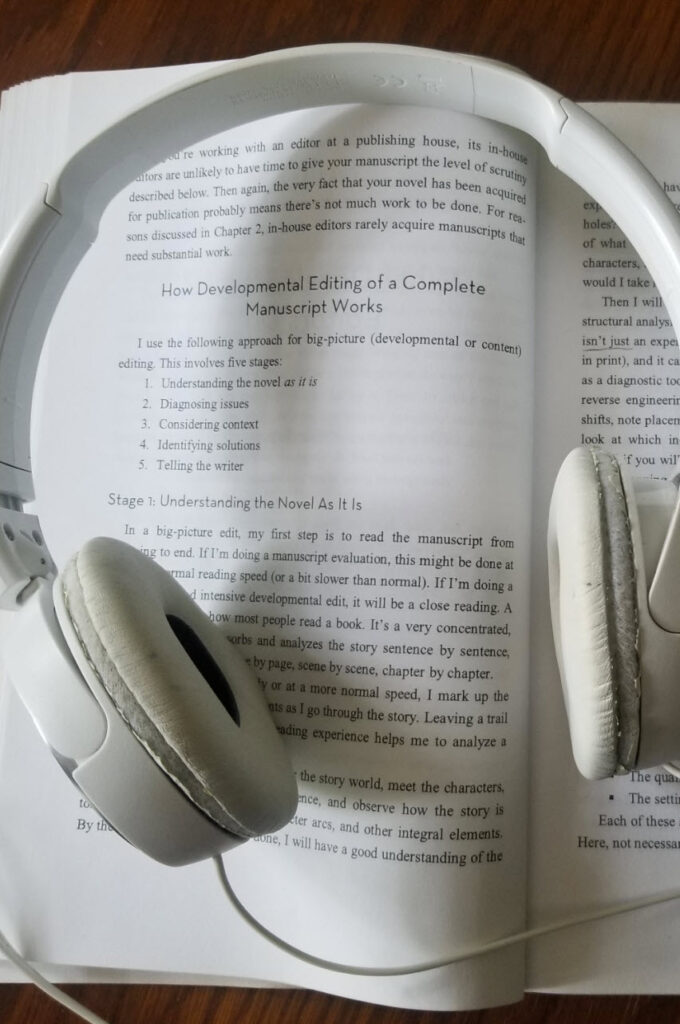

Listen to: What Development Editors Do

If the short-term goal of developmental editing is the best current book, the long-term goal is the maximum development of the writer’s talent and independence.

PAUL D. MCCARTHY

Writers are an individualistic bunch. Whether you’re a planner (outliner) or a pantser (writing “by the seat of your pants”), there are as many ways of writing a novel as there are people.

Editing is also an individual pursuit, but there is a natural flow of events that most fiction editors will follow, to one degree or another. So it is possible to describe a “standard approach” involving sequential steps—depending, of course, on the contract’s scope of work and the editor’s personal style.

Developmental editing is sometimes called book doctoring or content editing. As described in Chapter 5, it can range in detail from a full developmental edit to an overview critique or a manuscript evaluation.

This chapter describes two approaches to developmental editing. The first details my typical approach to a developmental edit of a completed novel. The second describes how editors do ongoing story development, coaching, or consulting with writers.

If you’re working with an editor at a publishing house, its in-house editors are unlikely to have time to give your manuscript the level of scrutiny described below. Then again, the very fact that your novel has been acquired for publication probably means there’s not much work to be done. For reasons discussed in Chapter 2, in-house editors rarely acquire manuscripts that need substantial work.

How Developmental Editing of a Complete Manuscript Works

I use the following approach for big-picture (developmental or content) editing. This involves five stages:

- Understanding the novel as it is

- Diagnosing issues

- Considering context

- Identifying solutions

- Telling the writer

Stage 1: Understanding the Novel As It Is

In a big-picture edit, my first step is to read the manuscript from beginning to end. If I’m doing a manuscript evaluation, this might be done at an almost-normal reading speed (or a bit slower than normal). If I’m doing a more detailed and intensive developmental edit, it will be a close reading. A close reading is not how most people read a book. It’s a very concentrated, focused reading that absorbs and analyzes the story sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph, page by page, scene by scene, chapter by chapter.

Whether I’m reading closely or at a more normal speed, I mark up the manuscript with marginal comments as I go through the story. Leaving a trail of my thoughts about the initial reading experience helps me to analyze a novel’s strengths and flaws.

During this first reading I will enter the story world, meet the characters, immerse myself in the reading experience, and observe how the story is told—its structure, plot threads, character arcs, and other integral elements. By the time this first reading is done, I will have a good understanding of the novel and will have identified any obvious issues interfering with the reading experience. Where did I drift, where did I stop believing, where did I see plot holes? Just as important—in fact, more important—is my developing sense of what works and why it works. What do I love about this story, these characters, the time and place of the story world? If I found it in a bookstore, would I take it to the cashier?

Then I will read the novel a second time, usually more quickly, and do a structural analysis. I will, at this point, often create a book map. A manuscript isn’t just an experience, it’s also a physical object (whether it’s electronic or in print), and it can actually be taken apart and analyzed. I use the book map as a diagnostic tool, usually for issues with structure or pacing. It’s a bit like reverse engineering. It allows me to look at word counts, see when POV shifts, note placement and length of flashbacks, trace character development, look at which incidents are dramatized in scene and which happen “off stage,” if you will, and try to confirm or refute my initial impressions about what’s stopping the reader from fully engaging with the work.